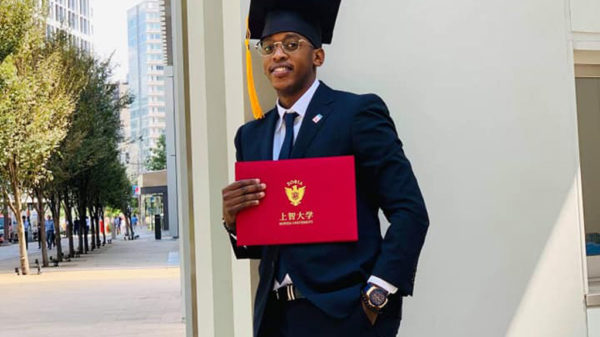

Verckys Kiamuangana Mateta at a performance. He was notable as the first indigenous African to own a record label. Photo / Courtesy

A rebel who shook up the Catholic Church in Congo and challenged the monopoly of European record labels, Verckys was as synonymous with breaking up music bands as he was with the saxophone.

It’s a very short clip—32 seconds. But the sound is very clear. Verckys and Veve in Entebbe circa 1974 belting out praises for President Idi Amin, his love for his people, love for Africa…

Forget it.

Mbilia Bel was performing in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania, in 1992 when the revellers went wild. Consumed in the crescendo, she wiggled her waist with more vigour until she noticed that the attention of the revellers was elsewhere. There was a familiar figure for whom the revellers were animated. Bel was livid it wasn’t her gyrations.

If you ran a poll asking who the man was, 99.99 percent of respondents would pick Georges Kiamuangana Mateta. To a fault, of course. The man popularly known as Verckys, was such a disruptive figure in Congolese music.

And while Kanda Bongo Man—for he was Mbilia Bel’s disruptor—was a one-off, disruption was the DNA of sax wizard Verckys.

From having rival musicians banned from recording and performing, to poaching talented ones to weaken rival bands, Verckys had his hands full between the 1970s and mid 1980s when he was one-third of the ‘Three Musketeers’ alongside Franco of TP OK Jazz and Tabu Ley of Afrisa.

“Verckys was one of the most disruptive musicians of his era,” says Michael Wakabi, a journalist.

Asuman Bisiika, a columnist and Tabu Ley-mad follower, has no kind words for Verckys. But Kenyan rumba historian Jerome Ogola argues his “contribution to rumba, in the positive side, outshines the negatives.”

The sax wizard’s disruption was first noticed at TPOK. In 1968, Franco took some of his band members on a tour of Europe. Verckys had been with the band for seven years and was unhappy at being left behind. He also later admitted that his songs did not have the same lustre and success as those of Franco.

“Franco had the secret of the depth of the songs, he was really the great master,” the man who composed Madame de la Maison at TPOK, said.

Verckys led some of the musicians Franco had left behind in a recording session that produced four songs. He would later sell the tapes and buy two cars. Franco was not amused on return. Verckys left to form Orchestra Veve.

War with Catholic Church

Among the young musicians Verckys recruited for Veve were Matadidi ‘Mario’ Mabele, Marcel Loko Djeskain, and Bonghat ‘Sinatra’ Tshekabu. The three youngsters came to be known as ‘Trio Ma-Dje-Si’ and one of the biggest victims of Verckys’ disruptive wrath.

Trio Madjesi had brought a rare feel to Congolese music as they used humour to wow revellers, giving a good run to Franco and Tabu Ley.

Their joy was short-lived as Franco, Ley and Verckys bonded into the Three Musketeers. With leadership of the musicians’ union in their hands, Trio Madjesi were found guilty of breaching the code of conduct, banned from recording or performing for six months.

Orchestre Sosoliso folded.

Verckys then courted the wrath of the Catholic Church by producing a song that stopped short of questioning the existence of God. In the 1972 song, Nakomitunuka, Verckys probes the race question.

“In the holy books, saints are depicted as White, angels are White, Adam and Eve are White, Jesus was White… If it’s a demon, it is depicted as a Black person. Where did the injustice come from?” he whined before being excommunicated.

Verckys found solace in his music, his growing businesses and, yes, the Kimbangiste—a sect founded by Simon Kimbangu, whose believers considered him a reincarnation of the Holy Spirit.

The visionary

Verckys cherished rumba. His contributions towers his sax and the 165cm reach to make him a pillar in the growth of Congolese rumba.

“A lead guitarist as well, he made the saxophone the lead instrument in his productions. He used the instrument in very subtle ways. Listen to Taty and Ditutala,” says Wakabi.

In 1971, Verckys disrupted the European record labels when he bought equipment from Roger Izeidi and set up a record label, Editions Veve, in Kinshasa—becoming the first native African to own such a record label, a milestone that would impact the careers of several musicians and bands in the Congo.

But it was also akin to daring sharks to an underwater battle. While record labels such as Ngoma, Olympia, Opika and Loningisa had been set up in Zaire from as early as the 1940s, by the 1970s, most rumba was handled by record labels from Europe.

“You must know that the music [industry] is just like the mafia. To be able to penetrate that system, you must be very powerful because there is protectionism mainly from the French,” Vercky explained, adding, “The French are the people who deal most with Africa at the moment. There are companies in France that export records to Africa, although the musicians are from Africa. I know I am running a very big danger from foreign producers because we may now have to share the beefsteak.”

With Editions Veve, Verckys promoted several musicians, including Vata Mombasa, Nzaya Nzayadio, Nyboma Mwan’Dido and Pepe Kalle. Verckys recorded and produced Grand Maquisards, Kiam, Bella Bella, Lipua Lipua, Les Kamale and Empire Bakuba. Orchestre Veve grew so big it ran other bands.

Great hits

Ndona, Lukani…

In 1975, Lipua Lipua produced Nouvelle Generation and Veve produced Lukani. In the latter, Verckys demonstrated a mastery of the sax in a way that blowers such as Jean Serge Essous, Hugh Masekela, Empompo Loway, Manu Dibangu, lsaac Musekiwa, and Rondot Kassongo would approve.

But this was two years after arguably his greatest production, Ndona (composed by Kelly Makiadi), a mournfully blissful ballad in which a man is terrified by the beauty of his love for she is the attention of every man. Ndona is really nice, but the real catch is when Verckys broke down during the recording so his raw emotion was captured. He was mourning his mother, who had died days earlier.

Background

Lungs of steel no more

Verckys was born on May 19, 1944, in Kisantu, a town west of Kinshasa. Coming from a wealthy family, he picked up music while he played with the church choir.

He adopted the name Verckys after American saxophone player King Curtis. But it had taken an inadvertent disruption to the name Curtis when he confused the accented pronunciation, which he heard as ‘Verckys.’ It would be long after his stage name had struck home that he learnt the real name was Curtis.

Verckys suffered a mild stroke four months ago that dimmed his sax on Thursday at the age of 78. He is survived by 19 children, one musician said. Another put the number at over 30.

The public only seem to know Ancy, a daughter with whom Verckys famously played at various concerts around the world with.