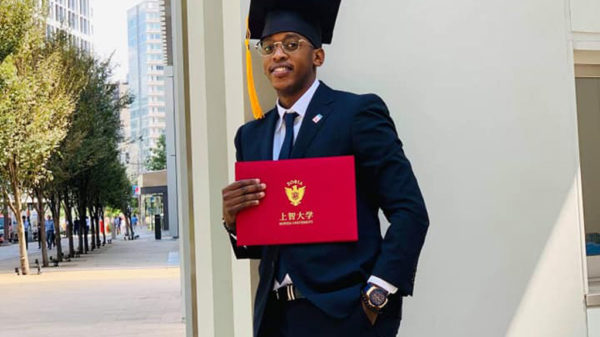

Luswata, one of the directors of the play says he had trouble with casting for the show. Photos / Andrew Kaggwa

If you are a fan of New York’s Broadway and London’s West End, you are definitely an ardent follower of theatre. Broadway is said to be the heart of American theatre while a life in theatre in the UK starts and ends on the West End.

Productions such as Hamilton, about the rapping founding fathers of America and Six, about King Henry’s six wives became worldwide cults after premiering in the venues respectively. Theatres elsewhere took on the culture, mainly because playwrights, especially in Africa, were trained by their colonial masters.

In the early years of the National Theatre, plays with elements of music were famous, yet as time went by, the culture was later abandoned.

Some continued having music in their productions but never gave the music the attention it needed. Sometimes actors simply sang their lines without instrumentation. For many people going to Ugandan theatre today, music is something they may forget moves hand in hand with the craft.

Yet, Phillip Luswata’s latest production, Shame on Your Hand, seemed to jump out of the box.

The show, directly inspired by the increased numbers of sexual assault and harrasment brings together theatre elements of music, spoken word and instrumentation to give Ugandans a feel of New York’s Broadway.

In fact, the director and playwright even went as far as getting the services of Branco Sekalegga, a renowned music composer, to work on the music. The purpose of this was to help the audience appreciate the art at its basics.

But, of course, unlike Broadway whose songs these days sound like hits pulled out of a famous radio playlist, these remained ordinary to the ear.

The play Shame on Your Hand is one that most Ugandans may not have known they needed, yet, watching the plot unravel on stage, through the stories of the different female characters, it was clear it was a show we needed.

The show’s themes are those that have been famous on both mainstream and social media, but most recently, artiste Sheebah Karungi called out a prominent male member of the society she claimed was trying to be funny with her.

Much as the artiste never named who the prominent male was, she had already got her message across, someone had tried to have his way with her. Luswata, in an interview, noted that if someone like Sheebah can be attacked and the abuser does not get named, it shows how much this is a bigger problem, especially to girls without the same power and platform as the artiste.

But, of course, even the reactions of both men and women, the divided opinion was telling. And all these lines of thought feature heavily in Luswata’s play.

The play presents us with six women, who have a thing or two to do with Andrew, the only male member of the cast. One of the women was raped by him, the other mothered a child with him, some were assaulted by him while the vocal one is his mother.

Their differing connections with Andrew most of the times determine their reaction to Andrew’s action, as we get deeper into the story, there aremany things we learn about Andrew’s behaviour, we learn that he raped the mother of his children while we also later understand why unlike other mothers wanted, his wanted him dead.

Andrew’s mother is a rape victim who concieved.

The play asks many questions and tries to answer many, though somewhere on the way, they may have trapped themselves in generalising men, either with or without intention.

Luswata says at the beginning of the play’s reading and rehearsals, they struggled with the cast, but of course, that was at a time when he was directing the show alone. With advice from the cast, actress Sharon Atuhaire became the female director of the show and it is clear there are things she may have easily made the cast say than any male director would.

The show was staged at the National Theatre for two weeks and just like many conversations as these, many people in the audience noted that it was uncomfortable. A sign that both the cast and crew hit the right notes.

editorial@ug.nationmedia.com