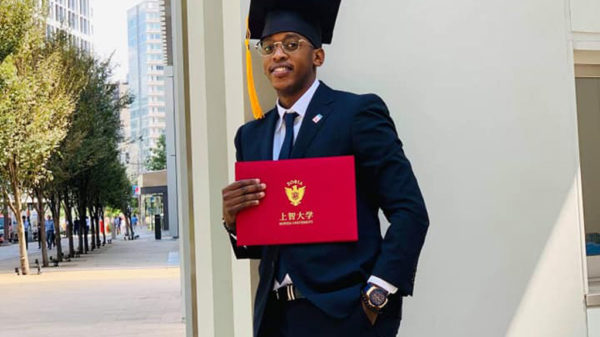

Eriya Bugembe Sebunya aka Kasiwukira. PHOTO/FILE/COURTESY

On Saturday, August 7, Saturday Monitor published a caveat emptor or public warning by law firm, Erick-Kiingi and Co Advocates on behalf of Kasiwukira Ltd.

The full-page advert warned against anyone intent on selling or reselling works of more than 120 musicians, with 118 music albums and hundreds of titles.

The lawyers stated all the works listed in the advert “belong to and are the property of Kasiwukira Ltd”.

The lawyers further warned that “…the aforementioned works are not for sale to any person(s) whatsoever.”

The warning read: “This is to notify the general public that all vested contingent and future rights of copyright and all rights in the nature of copyright and accrued rights of action, and all other rights of whatever nature in and to work, whether now or in the future created in Uganda is the property and works comprised in the following works.”

They added: “On the aforementioned premise, therefore, any person(s) who transact(s) or engages in any dealing(s) whatsoever in respect of the same does so at his or her own peril.”

Since the death of businessman Eriya Sebunya Bugembe, alias Kasiwukira, in 2014, very little has been heard from the empire that is credited to have built demand and music-purchasing culture in Uganda.

It was also said at one point that they had closed all their music related businesses, especially at a time when technology invaded the creative economy.

Kasiwukira, is said to have started importing cassette tapes in 1983 and thus, knew how to duplicate music onto many of these.

In 1983, knowingly or unknowingly, Kasiwukira set up a business model akin to that of a record label such as Sony or Universal. For instance, like these record labels, he could distribute music for some artistes with potential, he could fund the whole recording, promotion, release scheduling and marketing process.

This made Kasiwukira a promoter and publisher way before Ugandans could learn how to throw these words around.

How all this happened, an ambitious performer left a rural area for Kampala to chase a dream. Most of these ended up in Kadongo Kamu bands such as Kulabako Guitar Singers, Matendo Promotions and Bazira Guitar Singers.

In such bands, they had a chance to curtain-raise for an artiste such as Paul Kafeero, Livingstone Kasozi and Herman Basudde, among others.

However, performances were not the sole source of income for artistes at the time, album sales were too, thus, when an artiste gained prominence with the live audience, they would head to the studio to record an album. Usually a six-track album.

And that was how Kasiwukira and others such as Dick Promotions came into the picture.

Most artistes simply recorded music and later approached Kasiwukira with this music. He would then buy it, promote it, schedule release of its singles on radios and later release it to the public.

But all this came at a cost. This meant Kasiwukira bought music from artistes at a fee, then incurred the costs of branding, promoting and marketing it in the hope of making all his money back through copy sales of the album.

For some artistes who couldn’t afford studio fees, he gave them advances to record music, hoping he could recoup his money when the music made money.

Most of the contracts artistes made at the time signed away ownership of their intellectual property and almost 30 years after they were made, some have learned they are not the owners of their craft.