The art piece Abakulembeze, which depicts hands in chains, a true picture of what trafficked girls go through. PhotoS/ ANDREW KAGGWA

Women so many times continue to be undermined and taken advantage of. As we celebrate the month of women, two artists showcased work of art that shades light on the plight of trafficked girls.

If there is an image frequent air travellers are used to over the years, it is definitely one of very many uniformed people checking in as a group to travel to a country in the Middle East. Most times, these groups are coordinated by a local labour export company that connects them to possible companies, schools or homes in the host country.

Many of these travel in search of a better life, but most times, they return with horrific stories, if they even get a chance to return.

On Saturday, human trafficking and its effects were a main topic of The Passport exhibition that opened at the Xenson Art Space in Kamwokya, a Kampala suburb.

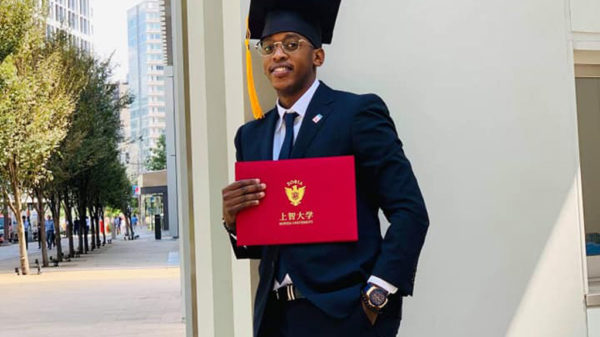

The exhibition brought two artists; Yuda Tadeo Karisimbi, a sculptor and Katesi Kalange, a painter and sculptor together. Their role was to tell a story of human trafficking through wood, metal works and paintings.

The art

From the first installation of a hand in chains, holding a Ugandan passport, the two artists announced their intentions in a bold way, seeming to tell the audience that these topics need to be discussed and if people have to be called out, it has to happen now.

The exhibition is thus a vehicle the artists use to drive a message and while at it, start a conversation around human trafficking; whose fault is it and who else shares the blame?

Of course, along the way many things are tackled such as the human trafficking happening within our homes and how it may not be so different from those trafficked to the Middle East.

For instance, a survivor at the exhibition that requested anonymity, said while in Uganda, she worked as a teacher despite being a social science graduate.

“I had a dream of improving my mother’s lifestyle and the teaching job was not going to make this a reality soon,” she says.

She decided to apply for one of the jobs through a labour export company. Initially, she says, she was told she was going to be a home teacher and signed a contract of the same.

“But the moment you reach the destination, your passports are taken and that’s almost the last time your contract matters. Before you know it, you are a maid,” she says.

She, however, says on noticing that she was being forced to do things she had not signed up for, she linked up with the agency that had received them but most of the time, they simply reminded her that she came to make money thus must do the job available.

She managed to come back to Uganda eight months later and says she was only lucky because she had made a lot of noise on different social media groups.

In one of the paintings on display at the exhibition titled Abakulembeze, Kalange paints a hand in chains and a Ugandan passport reaching out to another wrapped in a Ugandan flag.

Yuda Tadeo Karisimbi and Katesi Kalange, the brains behind the exhibition.

The passport

The Ugandan hand in chains is cast in red shadows that the painter says represent the uncertainty these people face in these countries while looking at Uganda with hope.

“Yet most times even when they reach out to Ugandan government officials, they don’t get the help they need,” Kalange says.

According to the survivor, different girls end up in the Middle East for work, but Ugandans are the most marketable, sometimes they are even sold from one employer to the other. Sometimes they are even sold to countries different from those in the contracts.

“I learnt that they enjoy having Ugandans because regardless of the number of girls that suffer while working in these countries, our leaders will not speak out or be as vocal as the Nigerians and Kenyans, for instance,” she says.

The message

Karisimbi’s works seems to rhyme with Kalange’s beliefs as well. For instance, two of his works titled Mbuto Zabwe looks at the people that benefit the most when humans are trafficked.

“It is a dangerous trade, yet deep down, we know that for every person trafficked, there is a person earning,” he says.

He brings the topic down to Uganda where girls are trafficked from their villages to city homes to work as maids: “Most times, there is a middle man that is paid to deliver the girl to the Kampala home she must work at.”

Karisimbi’s Misinformation and Kalange’s Broken Trust seems to explain why despite the heart breaking stories, girls continue to flock the Middle East in the hope of getting better results.

“They never get all the needed information before they leave the country, on reaching the destination, they realise the agents lied to them,” Kalange says.

However, Karisimbi says even when people are lied to, some misinform themselves by selectively listening to what they want to hear; “You will always hear about stories of people that have suffered at the hands of their employees in the Middle East, yet many trying to go there will concentrate on the success stories, shutting out the rest.”

The survivor though, says it is a human element of always thinking you will be wiser than those before you.

“I also believed I would be wiser, smarter but I ended up as a maid locked in a room,” she says.