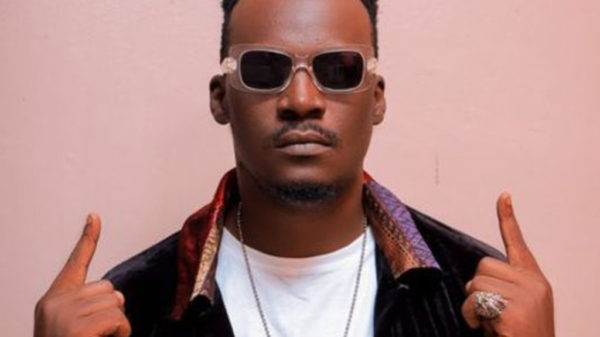

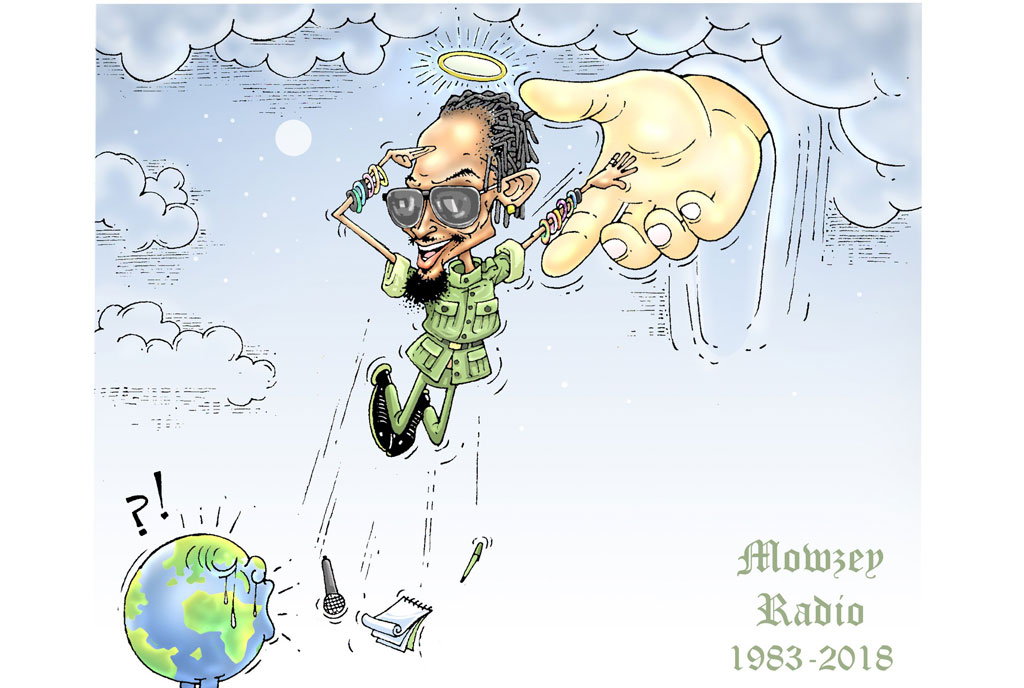

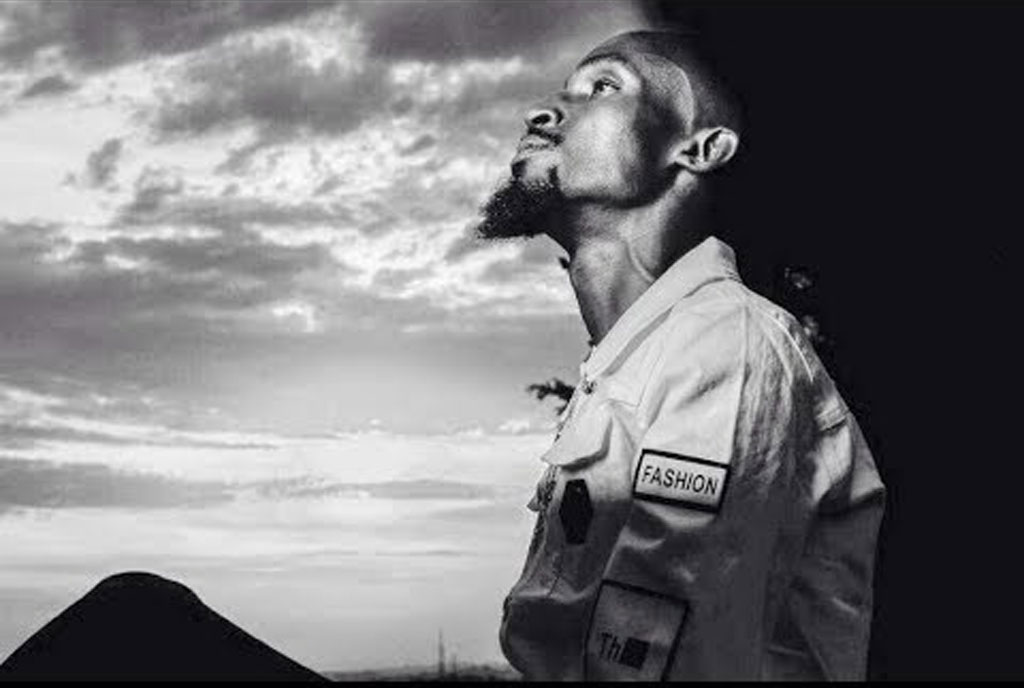

NEVER FORGOTTEN: Today marks exactly one year since Mowzey Radio passed away at Case Hospital following a bar brawl at De Bar in Entebbe. The death of Radio was a bitter pill to swallow and to date, not many people have come to terms with it. Andrew Kaggwa had a chat with one of Radio’s girlfriends and baby mama, Jennifer Robinson.

At 11.25pm in 2011, Mowzey Radio was involved in a fight. But that was not the first and neither the last fight he had been involved in. It is even easy to imagine no one knows the specific fight we are trying to talk about because it was 2011, Radio and Weasel were at the top of their game and like all Ugandan artistes at the top, they fight.

And no one even knows the exact time the fights happen, it could be 11.25pm, mid-day or the afternoon, it is hard knowing when local celebrities are going to lose it.

On their part, Radio and Weasel fought with Bebe Cool, Rabadaba, DJ Shiru, Jose Chameleone, Jeff Kiwa, entertainment establishments such as bars, media houses and while at it, they made good art out of it.

Thus, when news broke in the wee hours of January 22, 2018 that one half of the Radio and Weasel duo had been admitted to Case Hospital after a brawl, it was easy for people to dismiss it as one of those undocumented fights.

Yes, he had been admitted but he was not the first. In 2005, Bebe Cool had been admitted after sustaining knife injuries during a fight with members of Chameleone’s Leone Island. Years later, Chameleone too had been admitted after he broke his legs under mysterious circumstances, one Thaddeus of the Goodlyfe had also been admitted after being stabbed by unknown people or person during a fight in a bar.

Thus, for the first days of Moses Nakintije Ssekibogo alias Mowzey Radio’s admission to hospital, the public that had gotten accustomed to artistes’ violence was not moved.

Learning about the accident

For Jennifer Robinson, Radio’s girlfriend, things were serious from 11:25pm, the time she received a call from Frank, the deceased’s brother, asking her to come to the hospital.

Earlier, she had talked to Radio seeking to know whether she could pick him up or whether he was going to get home by himself.

“We chatted for about five minutes, I could hear the sound of a bar in the background,” she says.

“He had mentioned in the morning that he was going to Entebbe to buy cement so I assumed he was still there but he told me that he was about to leave, and he would be home soon.”

She had plans with Radio that day, when he got home. They were supposed to watch Blue Planet 2, a British nature documentary together, but since she realised he would be late, she knew those plans had to be moved to a different night.

But as she turned off the light, there it was – a phone call.

“It was not Moses but he often called from someone else’s phone when his battery died. I picked up and heard a siren in the background. I sat bolt upright because I knew there was something wrong.”

His brother had been on the other side of the line and as she says, had told her, “Moses has had an accident. You need to come here”.

She threw on random clothes and headed to Case Hospital though got lost on the way and because it was late, she was afraid of getting out of the car to ask for directions.

“I was in tears already and I realised I had no choice but to ask someone for directions. Fearing for my safety on top of everything else, I pulled up next to the most brightly lit boda stage I could find, opposite a casino.”

At Case Hospital, Jennifer says Frank was waiting for her. She threw the keys at someone to park the car for her.

Pay or die

Although she had met Radio way back in 2011 at Hi Table along Kampala Road, it was on this night at Case Hospital that she was going to understand how Ugandan systems work or not.

“Within 10 minutes I had paid Shs2m to get Moses into the ICU, and by 1am I had been charged another Shs8m,” she says, adding that she had been led to a doctor’s room and he had told her: “I am not going to call the surgeon until the money is paid”.

“So what else could I do? At this time I had not even been able to see him. I paid immediately, my only concern being that he needed surgery.”

Getting hold of the money

“Who can reasonably be expected to have Shs10m cash at midnight? All I did was gamble that my card would be accepted,” she says, adding that to date, she lives to wonder if she could have gotten him to surgery earlier, maybe he would have had a chance.

She was taken to ICU where Radio was being prepared for surgery. They explained to her what was going to happen and as she was still sobbing, she was shown some paperwork, but cannot remember if she was asked to sign anything.

“The ICU nurse told me ‘This is a place for hope, you must try not to cry, because Moses can hear you’. I kept that in mind for the rest of our time at Case, and I am grateful to that nurse.”

What really happened?

While sitting outside the operating room with steadily arriving friends and family, among other things Robinson wondered was why a hospital would hold a patient until they had been paid upfront, but above it all, what had happened in the bar in Entebbe.

The friends who had been with Moses said it had been an altercation.

They say he had been rugby-tackled from behind while walking out of the bar, was lifted into the air and his head slammed onto the concrete.

The consultant explained that the impact cracked his skull and blood had leaked into his brain.

“We had spoken at around 9pm. By midnight I was in the hospital. So I knew despite the delay in demanding upfront payment, he had gotten into surgery relatively quickly, and we had reason to be hopeful.”

But she was wrong. He worsened, got seizures and it was only on January 31 that their questions of when he would wake up moved from “let us see what the day brings” or “that is in God’s hands” to “we believe he will wake up soon”.

He is gone

Unfortunately, on Thursday, February 1 at around 6.30am, Radio was pronounced dead.

“His mother called and told me he had died. I could not drive, so I took a boda to the hospital. I stood by his bed for the last time, trying to hold his hand, but his fingers were already cold, trying to look into the eyes that just stared through me, trying to memorise the lines on his face, recall the sound of his voice, pleading with him to come back. I remember trying not to hurt him, even with the flat lining machine beside him.”

“People were everywhere, it was bizarre to have spent years avoiding cameras and then to have them in my face and not care,” she says.

Facing Uganda’s violent nature

But the violence that took Radio from his family had been one thing Robinson had failed to understand about Uganda. Directly and indirectly they had talked about some of these things with Radio.

“One of our favourite and ongoing conversations was about differences between the UK and Uganda. He really liked hearing my perspective, but as a foreigner there were things that I just could not understand and often we wouldd have to agree to disagree.”

She reminisces a day she saw a neighbour beat her child and asked them to stop, only for the mother to be surprised. “I called Moses and told him what had happened and asked him if I had done the wrong thing by interfering. He said: ‘you know, sometimes I think Ugandans only know beating.

But I would have stopped her too, that is a baby’.”

The ordinary way Ugandans approach violence is something that still defeats her to date, she says most children are brought up in situations where problems are solved with beating and thus are likely to grow up and solve problems that way.

Of course, since Radio’s death, Robinson admits she has been asked various times for her opinion about things he did when he was alive.

She notes that being a celebrity never took away the fact that Radio was human and made mistakes.

“The same society in which he is ridiculed for his actions does very little to address the violence that underpins it.”

She notes that it is common for maids to be beaten, mistreated and unfairly dismissed: “It is commonplace, even actively encouraged, for children to be beaten both at home and at school.”

In her experience, she says almost every Ugandan she knows has been a victim of violence in some way, though many tend to look the other way when it is happening to someone in front of them – even their own children, which she believes makes all of us guilty of minimising the effects that violence has on our lives. Organisations such as FIDA and Raising Voices are working to change this, but it requires an overhaul of long-standing belief systems.

Moments after Radio’s death, Robinson says people continued judging his character.

“The Moses we knew had a hot temper, but he softened just as quickly. He was not very good at thinking about consequences either, but he was improving. His life as he wanted it was just beginning.”

She hopes that when Ugandans listen to Radio’s music, they think beyond the fact that he was great but also examine the fact that his death was avoidable.

“Uganda has a special place in my heart, but if there is anything to be learned from the tragic loss we suffered last year, it is that we cannot go on living in such a violent society. Violence is a learned behaviour which destroys lives, and it is up to all of us to begin the process of unlearning it for our children.

“Unfortunately, on Thursday, February 1 at around 6.30am, Radio was pronounced dead.

His mother called and told me he had died. I could not drive, so I took a boda to the hospital. I stood by his bed for the last time, trying to hold his hand, but his fingers were already cold, trying to look into the eyes that just stared through me, trying to memorise the lines on his face, recall the sound of his voice, pleading with him to come back. I remember trying not to hurt him, even with the flat lining machine beside him.

People were everywhere, it was bizarre to have spent years avoiding cameras and then to have them in my face and not care,” Jennifer Robinson says.